Three Interesting Stocks

Months of research condensed into ~3,000 words

This isn’t your typical “Three Stocks to Buy Today” post—the kind that gets thrown together over a weekend (or an afternoon) and barely skims the surface. These ideas are the opposite: the product of months of work, distilled down to their essentials without, I hope, losing any of the substance.

Toast ($TOST): $34/share • $20bn mcap • ~23× EV/EBIT (NTM)

Airbnb ($ABNB): $117/share • $71bn mcap • ~21× EV/EBIT (NTM)

Match Group ($MTCH): $33/share • $7.8bn mcap • ~11× EV/EBIT (NTM)

Let’s get into it.

Toast

I spend a lot of time listening to CEOs, and because I’m usually hunting for exceptional businesses at reasonable prices—the leaders I study tend to be of a high-caliber. Even so, it’s rare for one to make me stop and think, “Wow—this CEO is exceptional.”

That’s exactly what happened when I encountered Toast’s co-founder and CEO, Aman Narang. There are many reasons, but they boil down neatly into two points:

If I were a competitor, he’d be the CEO I’d least want to go up against.

If I worked in this space, he’d be the CEO I’d most want to work for.

(I suspect most of you would reach the same conclusion.)

Founded in 2013, Toast runs a cloud-based technology platform for the restaurant industry—an all-in-one POS. Growth has been exceptional: from under $1B pre-pandemic to more than $6B today, with plenty of room ahead. The company turned profitable last year and should ultimately reach adj. EBITDA margins of 40% or more. It’s also extremely well capitalized, on track to end 2025 with roughly $1.8 billion in net cash.

Most people (myself included, until recently) think of a POS as a fancy cash register. That may have been true once, but today—as Aman notes—it’s better understood as a restaurant’s central nervous system, coordinating orders, payments, menus, staffing, inventory, online channels, customer data, and more.

Toast now powers more than 150,000 restaurants across the U.S.—primarily SMB and mid-market operators—including more than half of those with Michelin stars.

As a keen observer of behavioral psychology, I feel compelled to underline just how powerful that social-proof effect is. Imagine you’re a restaurant operator evaluating vendors: once you learn that Toast is chosen by over half of the best restaurants in the country, how likely are you to pick an alternative—one not chosen by that illustrious cohort—absent a meaningfully lower price?

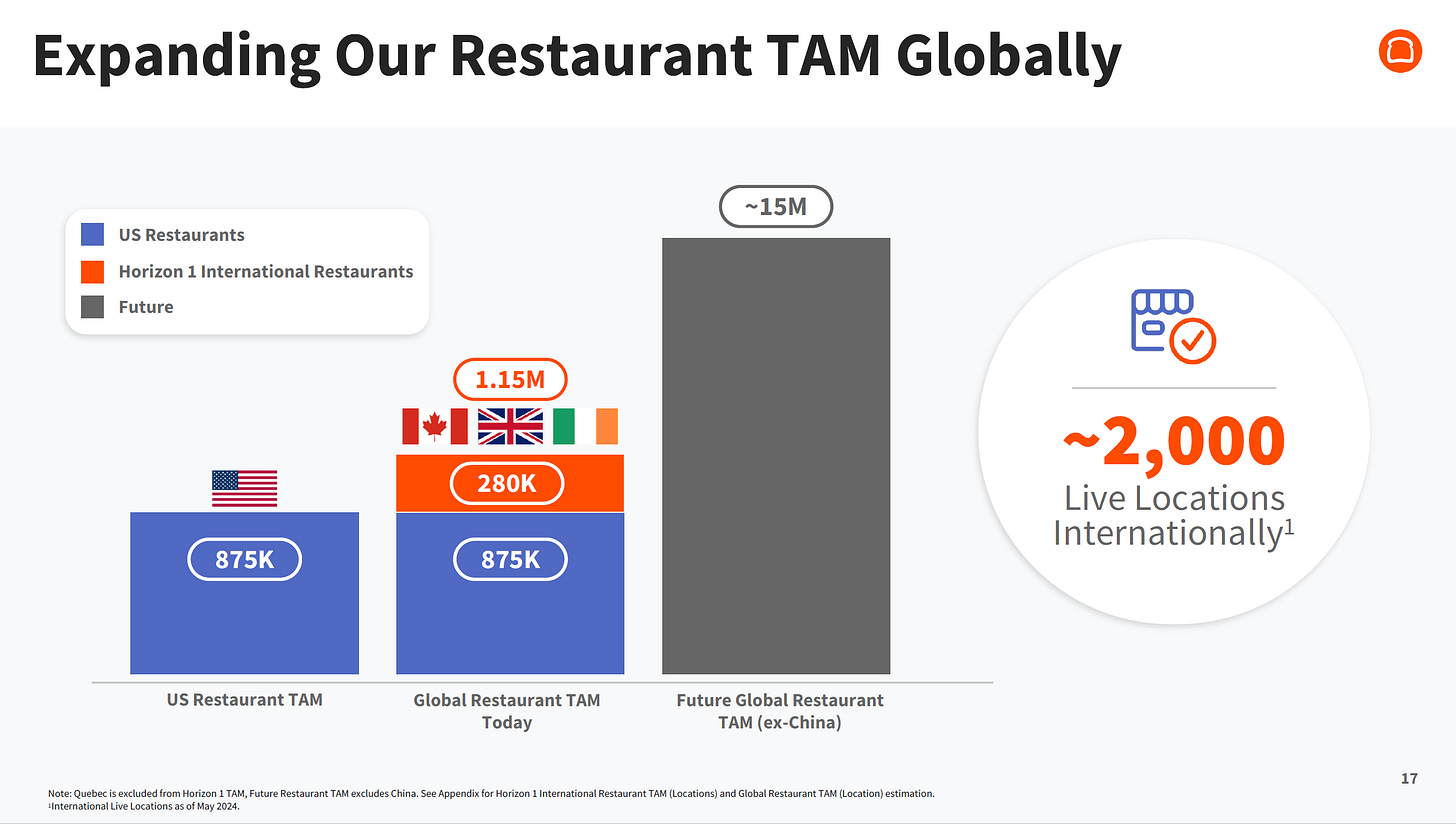

And there are still several hundred thousand restaurants in the U.S. alone that don’t (yet) use Toast—not to mention international markets, where the company has barely begun to scale.

Toast’s U.S. market share has more than doubled since 2021—from roughly 7% to more than 15% today—an especially impressive climb given how sticky POS systems tend to be. (Replacing one has been compared to removing a root canal.)

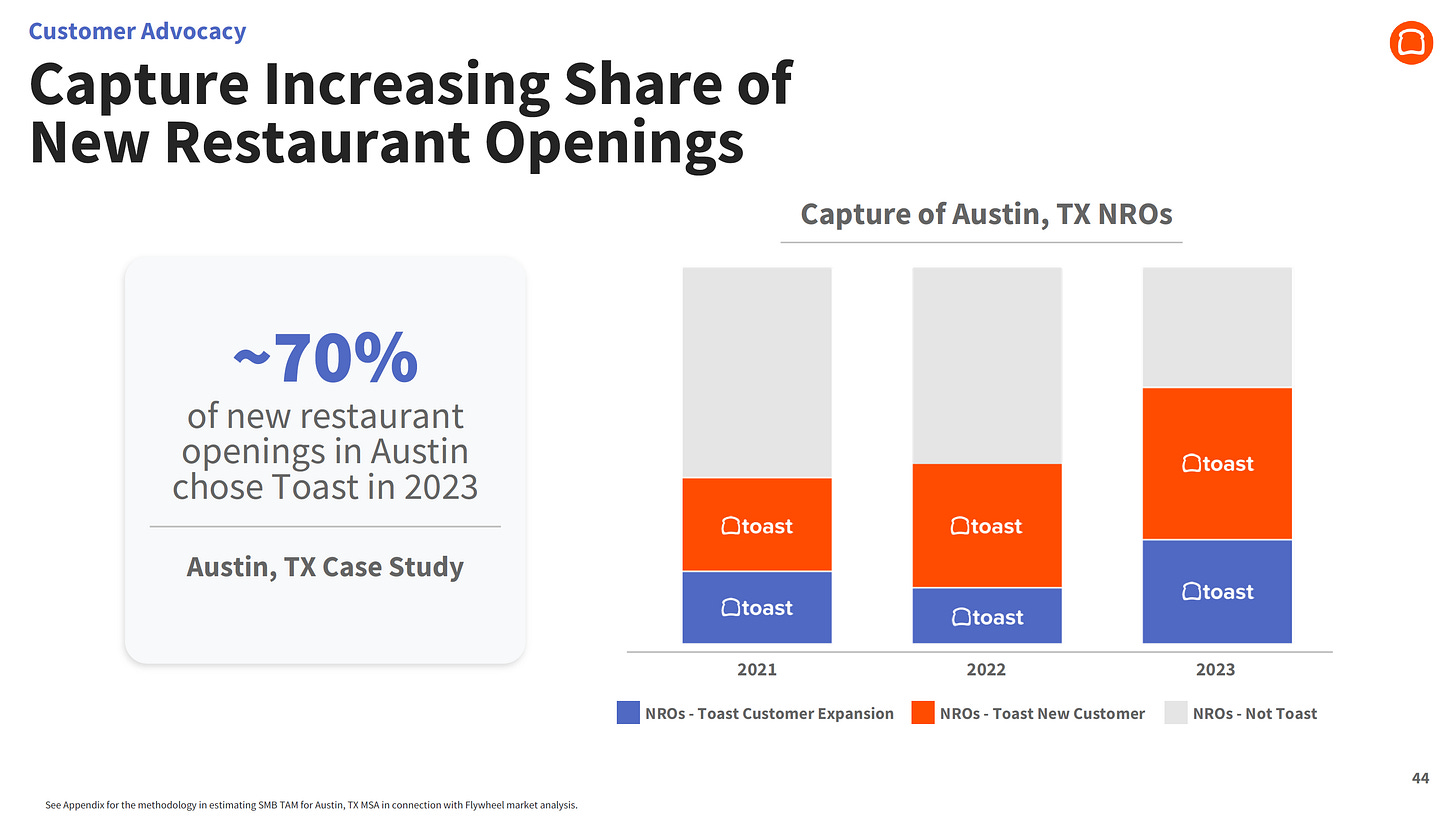

But the national figure understates Toast’s strength in its most developed cities. In many of these “flywheel markets”—dense pockets of customers that amplify word-of-mouth—Toast often holds 30%+ share. In Cambridge, MA (where Toast is based), for example, Aman observed: “you’d think Toast is the only point of sale.” Win rates and conversion are meaningfully higher in these areas.

And its share of new restaurant openings is higher still.

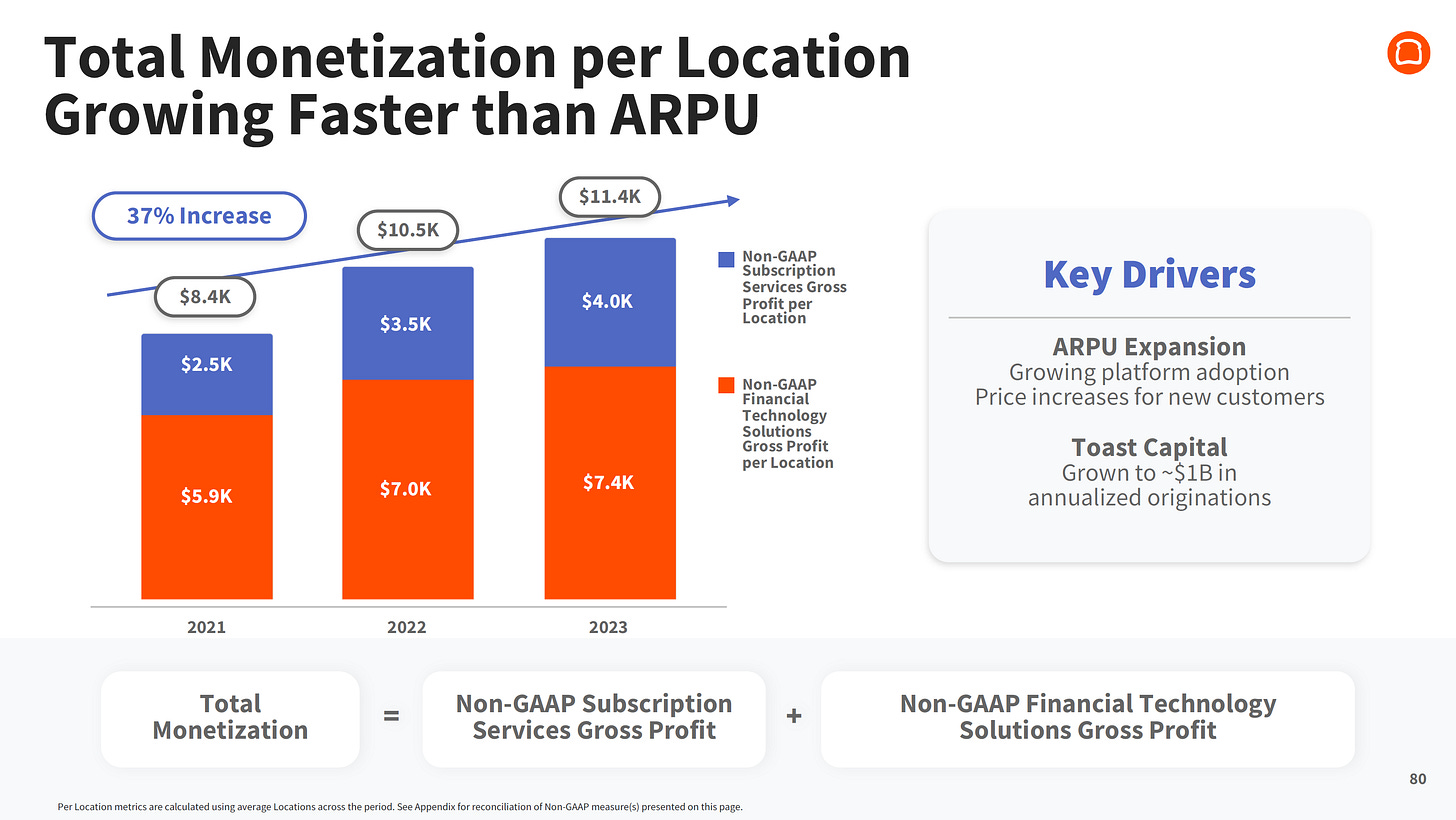

There’s also substantial room to grow monetization per location.

And Toast’s TAM isn’t limited to restaurants. Management sees several adjacent retail categories where they believe they have a “right to win.” Retail food and beverage is a notable example—still early, but traction so far has been strong.

According to management, these adjacencies—along with Toast’s budding enterprise business—could eventually rival or even exceed the size of its core restaurant business.

To sum it up: Toast has its competitors playing catch-up, and I expect that dynamic to persist. I also share management’s confidence in the company’s growth potential, both within the core and across these emerging categories. (In my experience, when you back exceptional CEOs at sensible valuations, the surprises tend to break your way.)

Valuation: Toast currently trades at 23× and 17× EV/EBIT for 2026/27 based on consensus estimates (OI margins of ~10.5% and 12%) and an implied 19% revenue CAGR. Assuming a stable macro backdrop, I expect the company to outperform on both growth and profitability (15–20% OI margins by 2027). If so, I’d expect at least 40–50% upside from current levels—and potentially much more.

The balance sheet also supports continued share repurchases, providing a measure of downside protection if the stock were to pull back. And unless the thesis changes, I’d view that as an opportunity. For long-term investors, the risk/reward remains compelling.

Airbnb

“I keep telling people that one day this company is going to be huge—it’s going to have thousands of users.” — Brian Chesky, CEO and co-founder, recalling Airbnb’s early days.

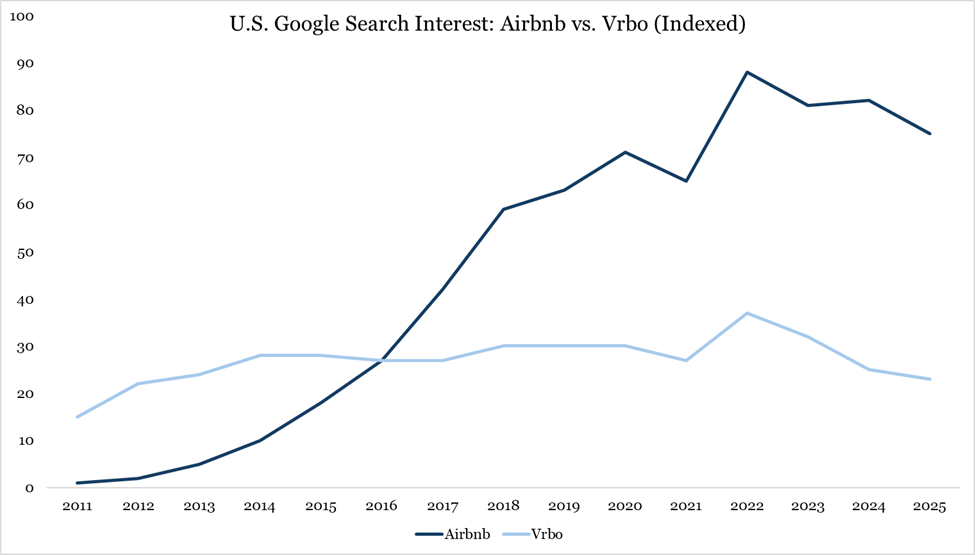

Airbnb hardly needs an introduction. Its name is now shorthand for the entire vacation-rental category—so much so that it’s become a verb. (Their recent marketing campaign plays on this: “Now you can Airbnb more than an Airbnb.”)

The company has delivered impressive growth post-COVID, doubling revenue from ~$6B in 2021 to about $12B today, with ample runway ahead. It boasts strong economics—OI margins around 22% and rising—and a fortress balance sheet with over $10B in net cash.

The platform now has over 8 million active listings—roughly 4× Vrbo’s ~2 million—even after pruning ~450,000 lower-quality listings in recent years. Airbnb’s verb status, massive installed base, and billions of reviews—roughly two-thirds of guests leave one—combine to form one of the strongest moats in consumer tech.

This is evident in the fact that ~90% of its traffic comes through direct or unpaid channels, far higher than Vrbo, Booking, or Expedia. (For the latter two, alternative accommodations remain add-ons rather than core offerings.)

And while most engagement has shifted to the app—used on more than 1.6 billion devices each year—the chart of Google Search interest from 2011–2025 offers a crisp view of how decisively Airbnb won the market-share war.

Airbnb now operates in more than 220 countries and over 100,000 cities. Yet its top five markets—the U.S., Canada, Australia, France, and the U.K.—account for 70% of revenue, underscoring substantial international headroom.

In the U.S., its most mature geography, Airbnb now accounts for roughly one in ten nights away from home. That’s impressive—though not the existential threat to hotels many once feared. Hotels still dominate short, highly urban, or one-night stays. But for longer trips (about 70% of nights booked are for month-long stays), and/or for families and groups, Airbnb’s value proposition is hard to beat: more shared space, kitchens, outdoor areas, and privacy.

So what’s interesting here, and why now?

The international runway is clear. Less obvious, though, is that Airbnb has a plausible path to doubling its share in mature markets (which is, in my view, not priced in). Several recent developments point in that direction:

1. Improved UI and reduced user friction

Airbnb has addressed many of its most persistent pain points—quality consistency, affordability, and pricing opacity. For instance, new pricing tools help hosts price more competitively, while the shift to a single-fee model (guests no longer see separate service or cleaning fees) makes the experience cleaner and easier to compare.

2. Co-hosting unlocking supply

Many people with homes would like to host but don’t have the time; many hosts (or would-be hosts) would like to host more but don’t have the capital for another home. As Chesky put it, “We’re basically existing in a very narrow Venn diagram of people that have time to host and have a home.” Co-hosting widens that Venn diagram. Launched late last year, it has already generated more than 10 million booked nights.

3. Adding hotels to fill inventory gaps

A large share of travelers begin their search on Airbnb but defect when they can’t find a suitable home—particularly for short, urban stays. To capture that spillover demand, Airbnb has begun listing boutique and independent hotels directly on the platform. During the latest earnings call, Chesky described his pitch to New York hotel operators—where Airbnb sees millions of searches:

“We believe that the majority of people who come to New York on Airbnb would be open to booking a hotel if there wasn’t a home available. Many of these people are subsequently opening other apps and booking hotels elsewhere. So, we said: if we added hotels, gave you a best-in-class commission, beautiful custom-built product pages, and brought you a lot of demand—often high-income, young American travelers, which are some of the most appealing consumer sets—would you be interested?”

The answer, unsurprisingly, was an enthusiastic yes.

4. Building the “Amazon for services”

The most consequential opportunity may sit outside homes entirely. Suppose you needed to book a photographer, private chef or caterer, makeup artist, or on-site massage therapist—where would you start? There is no dominant discovery platform, and certainly no unified marketplace that combines:

identity verification (Airbnb has over 200 million verified IDs—equal to or more than any other U.S. company)

integrated payments and scheduling

pre-screened, quality providers

standardized profiles with searchable supply

and, critically, trusted, platform-wide reviews

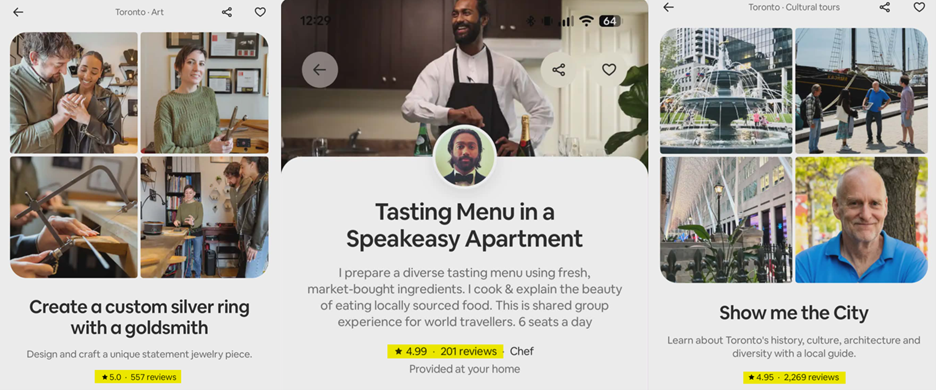

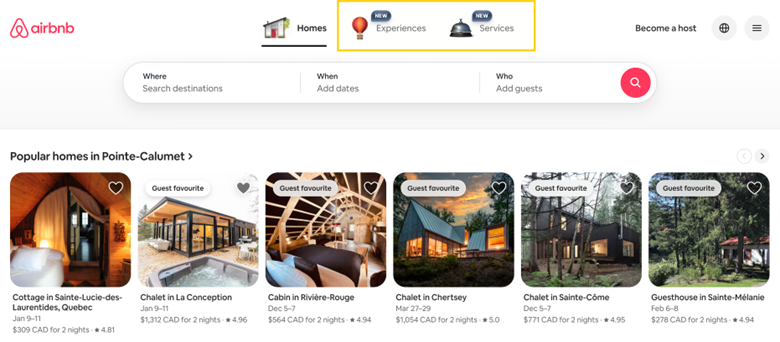

Airbnb launched Services earlier this year, alongside a relaunch of Experiences. Below are a few examples from Toronto (where I live): the tasting menu is a Service; the other two are Experiences.

Experiences were relaunched because several frictions needed to be addressed: they were hard to find, poorly merchandised, and not integrated with social media. (As you can see below, discovery will no longer be an issue.)

This placement, however, is not risk-free. Putting Services and Experiences on an equal footing with Homes—Airbnb’s highest-margin and highest-volume category—may hit conversions and could frustrate hosts. Yet management is clearly confident the long-term upside outweighs the potential trade-offs. (For what it’s worth, so am I.)

Many guests wouldn’t think to book a chef, photographer, or massage therapist when planning a trip. But when those options surface naturally in the booking flow, you’re prompting consideration when the guest already has intent. Experiences, conversely, are often explicitly searched for—so consolidating them within the same platform makes good sense.

Early results are encouraging. Roughly 10% of bookings are coming from entirely new customers, and locals are heavily engaging with Experiences. For example, in Paris—one of Airbnb’s largest markets—locals account for about 70% of Experience bookings.

Taken together, these developments are apt to both expand Airbnb’s audience and make the platform even stickier. As Chesky noted during the last earnings call:

“We believe that services, experiences, and hotels could each be multi-billion-dollar businesses.”

If that’s even directionally right, then the incremental lift to the core Homes business should likewise be measured in the billions.

Valuation: At around $115/share as of this writing, Airbnb sits well below its all-time high of ~$220/share and meaningfully under its five-year average of roughly $140/share. The stock now trades at about 21× EV/EBIT (NTM). Given the company’s growth trajectory and expected margin expansion, that strikes me as very reasonable.

Based on my work so far, I expect Airbnb to exceed earnings expectations in 2026/27 (assuming a stable macro backdrop). Consensus implies a 2027 EV/EBIT multiple of ~17×; my base case is closer to 15×. And unless I’ve misread/overlooked something material—which, as always, is possible—I’d expect the stock to work its way into the $150–$200 range.

Match Group

While it’s far more efficient to read transcripts, I try to listen to as many earnings calls as I can—because the text alone often leaves out a surprising amount of signal. Match is one of the clearest examples of why that habit matters. It also makes this pitch the hardest to capture persuasively in writing.

“We need to improve the perception of the [online dating] category. And the way to do that is to prioritize user outcomes over short-term revenue and profit. That has not been the way this company has operated historically, and that’s been to our detriment.” – Spencer Rascoff, CEO, Match Group

With more than 20 brands and roughly $3.5B in revenue, Match is the clear category leader in online dating. The business has solid economics—operating margins around 25%, with room to expand. Unlike the previous ideas, however, it does carry leverage: just under $3B in net debt, or roughly 2.3× adj. EBITDA.

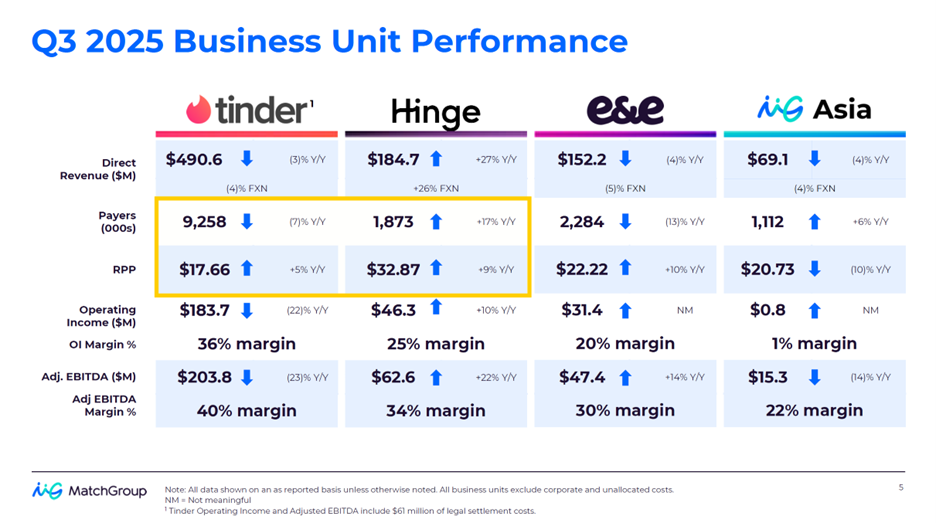

Match owns two of the three major Western apps—Tinder and Hinge (with Bumble as the third). Hinge is the growth engine; Tinder, the #1 dating app by downloads in more than 100 countries, is the cash cow with some brand baggage.

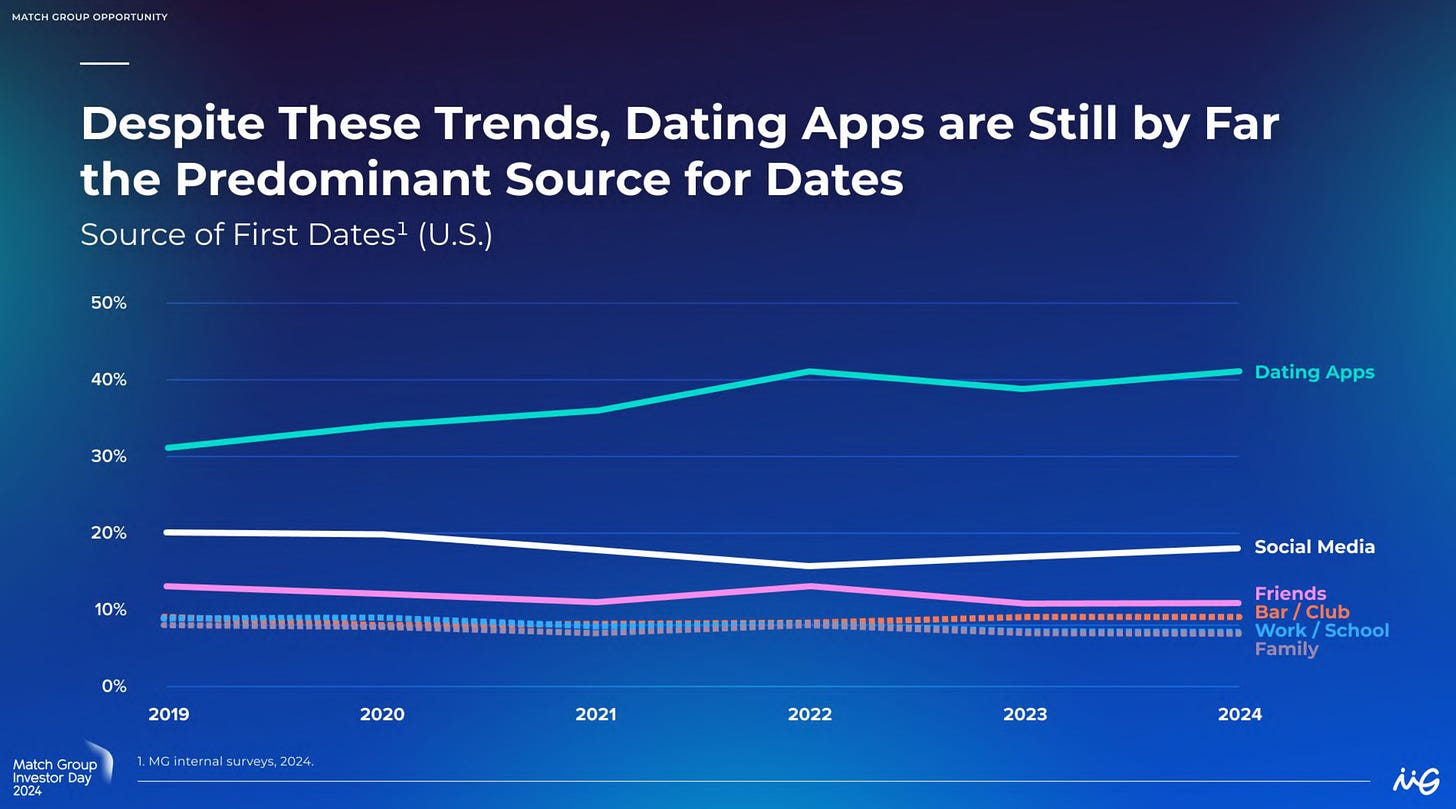

As many of you know, the online-dating category has been shrinking—or at best stagnating—in recent years, though it remains the primary way people meet. The open question is whether the industry is structurally broken or simply overdue for a reset.

Only time will answer that. But one person who clearly believes it’s fixable (yes, you guessed it) is Match’s new CEO, Spencer Rascoff—who wouldn’t have taken the role if he thought otherwise.

Spencer is the co-founder and longtime CEO of Zillow Group, which, for those unfamiliar, dominates the U.S. online real-estate marketplace. Put differently: he doesn’t need the paycheque, and he wouldn’t have stepped in unless he believed he could engineer a turnaround.

I cannot overstate the contrast between Spencer and his predecessors—three CEOs since 2017. All were capable operators and, by all appearances, good people. But that doesn’t necessarily make someone a great leader, capable of inspiring thousands of employees to do their best work.

The contrast with his immediate predecessor is especially stark—so stark, in fact, that the difference calls to mind Churchill and Chamberlain in 1940. Only one could rally a nation when it mattered. (If you’ve listened to their respective earnings calls, you know that’s not hyperbole.)

Spencer joined the board in 2024 and became CEO in February 2025. His first priority was rebooting the company culture—though he described it more forcefully: “shaking the company from a slumber.”

Match, he noted, is a category roll-up—spun out of IAC—that never fully extracted the benefits of its combined scale. Zillow, by contrast, is successful in part because it did exactly that. As Spencer explained:

“When I got here 100 days ago, it was really run as 20 different companies. Each app basically as their own company with its own Head of Marketing, its own Head of Technology, its own Head of Engineering. And I’ve changed a lot of that, and I’ll continue to, because there are enormous synergies to be had by recognizing the combined power of Match Group.”

Somewhat ironically, that independence is what allowed Hinge to thrive and maintain a “very impressive and distinctive company culture, with highly engaged employees,” as Spencer noted—in sharp contrast to Tinder.

During his first quarter, Spencer reduced the workforce by 13%, including one in five managers. But he was quick to emphasize that’s not what he came to do:

“I know how to cut costs, but that’s not what gets me up in the morning. What gets me up in the morning is being a product innovator, and building cool stuff that drives user outcomes, that grows audience, that grows revenue. I’m a growth CEO.”

Recent data might make that growth comment sound out of sync with reality. (The same goes for his remark: “I’m optimistic that one day we’ll look back and see the TAM in online dating was much larger than any of us expected.”)

Yet as you can see below, that optimism isn’t baseless.

Conventional wisdom frames the online-dating model as a paradox: the better the product is at making the right matches, the faster it loses its customers—and the worse that is for revenue. Hinge, which dominates the “intentioned” dating category, is a useful counterexample. Its success comes from a precise understanding of the job it exists to solve: to be the last dating app you’ll ever need. It is, literally, “designed to be deleted.”

That mindset—prioritizing user outcomes—is now being pushed across Tinder and the rest of the portfolio. I won’t unpack all the recent developments or new features here—several of which I’m optimistic about—but it’s clear the company is operating with renewed urgency and focus. As Spencer put it:

“By many measures, such as code commits or experiments that we have in-flight, we’re operating at about twice the pace as we were just a couple of quarters ago.”

I’m optimistic the products will continue to improve and resonate more with users, and that the perception of the category will gradually recover. As the category leader, Match has outsized influence in making that happen.

From a competitive standpoint, Match also holds the best hand. Its primary challenger, Bumble—also in turnaround mode—is roughly a quarter of the size and, in my view, far less likely to successfully land the plane. The more interesting threat comes from social-media giants like Facebook, which launched its dating product in 2019.

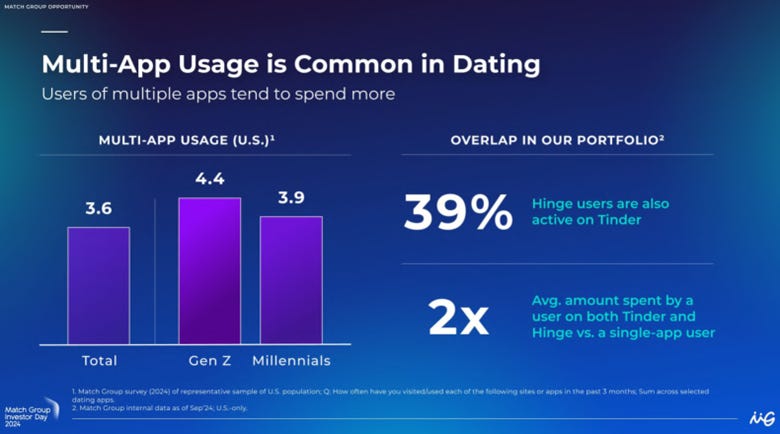

Its main advantage is simple: it’s free. It now has 21 million daily users, the vast majority over 30. (For reference, Hinge has 15 million.) It’s a trend worth monitoring, but it may sound more ominous than it is—especially given that dating is, and always has been, a multi-app category, as shown below.

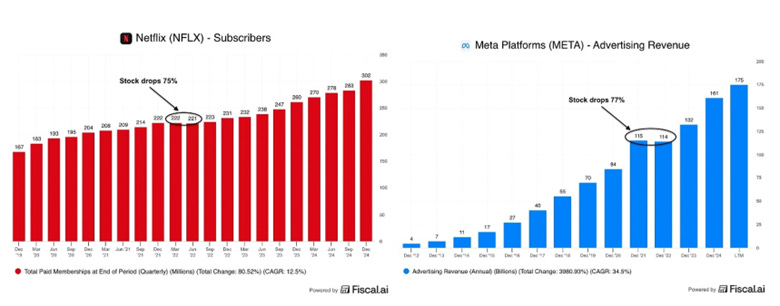

Taken together, I believe extrapolating recent trends here would be unwise—especially given the scale of the internal changes Match has undergone. Turnarounds, especially at scale, don’t happen overnight. The chart below, borrowed from Rebound Capital, is a useful reminder of why projecting the recent past forward without accounting for shifting dynamics can lead you astray:

I’m not suggesting the same outcome awaits Match—only that a meaningful improvement from here seems more likely than what the current valuation implies.

Valuation. Match currently trades at roughly 11× EV/EBIT (NTM). If the company can maintain momentum at Hinge—which still has substantial international runway—and simply stop the bleeding at Tinder, I’d expect the multiple to re-rate closer to 13–14× (roughly the 3-year average). If Tinder can return to even modest growth, I think 15× or higher is plausible.

In a nutshell, the potential upside significantly outweighs the downside over the next 12–24 months, assuming no fundamental changes to the thesis.

As always, thanks for reading. If you enjoyed this post, a quick thumbs-up—or a share with your network—goes a long way.

Disclosure: I or accounts under my control hold positions in the stocks discussed. This is not investment advice. Readers are encouraged to conduct their own due diligence. Some quotes were lightly edited for clarity and relevance.

Based on your write-ups alone and no additional research done on my side, I'd choose Match. I love the network effects in TOST, but it is richly priced and their client base must attrit a lot... restaurants are crappy clients to have, even if new restaurants replace the old ones and toast earns new clients as a result. Why pay up for a good business whose clients are typically very bad businesses? Match, at least, has the benefit of being cheap, despite being in turnaround mode. And, if things get very bad, they can close, or merge, either Hinge or Tinder, creating operational flexibility if paying users decline.

I bought 10 of each... Let's go!!