Lululemon (LULU): An Asymmetric Bet

Why I think the stock offers >50% upside from here

Note: I should disclose at the outset that I’ve been a happy and loyal Lululemon customer for several years, though I only recently became a shareholder. Readers should therefore assume the possibility of bias. That said, I believe my first-hand experience is more likely to be additive than distorting. As always, I’ve tried to minimize opinion and let the data and facts speak for themselves.

“People are crazy and emotional. They buy and sell things in an emotional way, not in a logical way, and that’s the only reason why we have any opportunity … So, if you have a way to value businesses that’s disciplined and makes sense, you should be able to take advantage of other people’s emotions.”

- Joel Greenblatt, in Richer, Wiser, Happier by William Green

It’s remarkable how quickly sentiment can flip.

Less than a year ago, in December 2024, Jim Cramer told Lululemon CEO Calvin McDonald that he thought the company was “the best story out there in retail right now.” He went on to elaborate:

“Everyone I talk to says China is a disaster; there’s no selling. Everybody tells me there’s no such thing as new; it’s all old. Everybody tells me it’s the most promotional Christmas in history; you have no promotions, you have newness, and you’re doing well in China. What are you doing right that the others are doing wrong?”

If Cramer’s starry-eyed tone didn’t already give it away, Lululemon was—until very recently—the crown jewel of the apparel category. Over the past decade, the company compounded revenue at roughly ~19% annually, despite already being a multibillion-dollar business at the outset. More impressive still, it did so while sustaining ~20.5% operating margins—more than twice the peer-group average of ~8% (Nike, Adidas, Under Armour, Puma). Businesses don’t produce numbers like that at scale without a moat of real depth.

The prevailing view today, however, is that the moat has drained. Even after a roughly 65% drawdown from its peak less than two years ago, short interest remains at a multi-year high of 6.2%. That might make sense if Lululemon were truly “running out of gas and it’s not fixable,” as one analyst claimed. The evidence, though, points elsewhere.

The bear case centers on falling U.S. comps, heavier discounting, and “hot” challenger brands nibbling at the edges. These are fair concerns—but context matters. The recent declines (–2% and –4% in Q1 and Q2, versus 0% and –3% a year earlier) come on the heels of a decade of near-uninterrupted hypergrowth. They also appear more symptomatic of internal complacency than external defeat—a lapse management has acknowledged.

“I now believe we have let our product life cycles run too long,” Calvin McDonald admitted. “We have become too predictable within our casual offerings and missed opportunities to create new trends.”

Given the company’s extraordinary run, it’s hard to fault them for sticking with a winning formula a little too long. (Most of us would have done the same.)

These declines also occurred against a softer category backdrop. “Consumers are spending less on apparel overall, spending less in performance activewear, and are being more selective in their purchases,” McDonald explained. Yet even then, Lululemon continued to gain share within premium activewear in both Q1 and Q2—just as it did in Q2 and Q3 of 2024, when comps were also slightly negative.

So while there’s clearly work to do, the notion that Lululemon is “broken” doesn’t hold up. Even a director at athleisure “disruptor” Vuori dismissed the claim outright: “I think the argument that they are getting stale is not a valid one.”1 An executive at competitor Fabletics agreed: “As a millennial myself, I don’t think Lululemon is getting stale.”2

Timing matters, too. Much of the current assortment still reflects the tail end of the former Chief Product Officer’s work, given an 18-month design cycle. The first full season shaped by the new creative director—and by Lululemon’s revamped design and merchandising model—won’t arrive until Spring 2026.

And by McDonald’s account, this design team—comprised of both seasoned and newly hired design leads—is “the best that we’ve ever had in the history of this organization.”3 If that’s even directionally true, and my research strongly suggests it is, then declaring the brand finished seems premature at best.

The question, then, isn’t whether Lululemon can course-correct, but whether it will. And if you’ve read this far, you can probably guess where I land on that question. Even if the recovery takes longer than investors might like, today’s valuation offers ample margin of safety for those willing to wait.

That margin already prices in the usual anxieties: fiercer competition, “dupes,” shifting style trends, Gen-Z fickleness, tariffs, and macro uncertainty. We’ll return to each in due course.

But before we dive in, a little historical perspective:

Jim Cramer, September 2016: “Should we be worried about Lululemon here, given the recent heinous action in the stock and the constant worry of the analyst community that athleisure has peaked?”

Professor Aswath Damodaran, April 2019: “I’d bet on Levi’s over something like a Lululemon, which will be a distant memory. The problem with brands today is that they build up really fast and don’t have roots. And millennial consumers don’t have loyalty.” (Notably, Damodaran said this despite Lululemon already being 20 years old—with a customer base among the most loyal in the industry.)

Investor anxieties, in other words, are rarely a reliable predictor of what happens next.

Thesis Overview

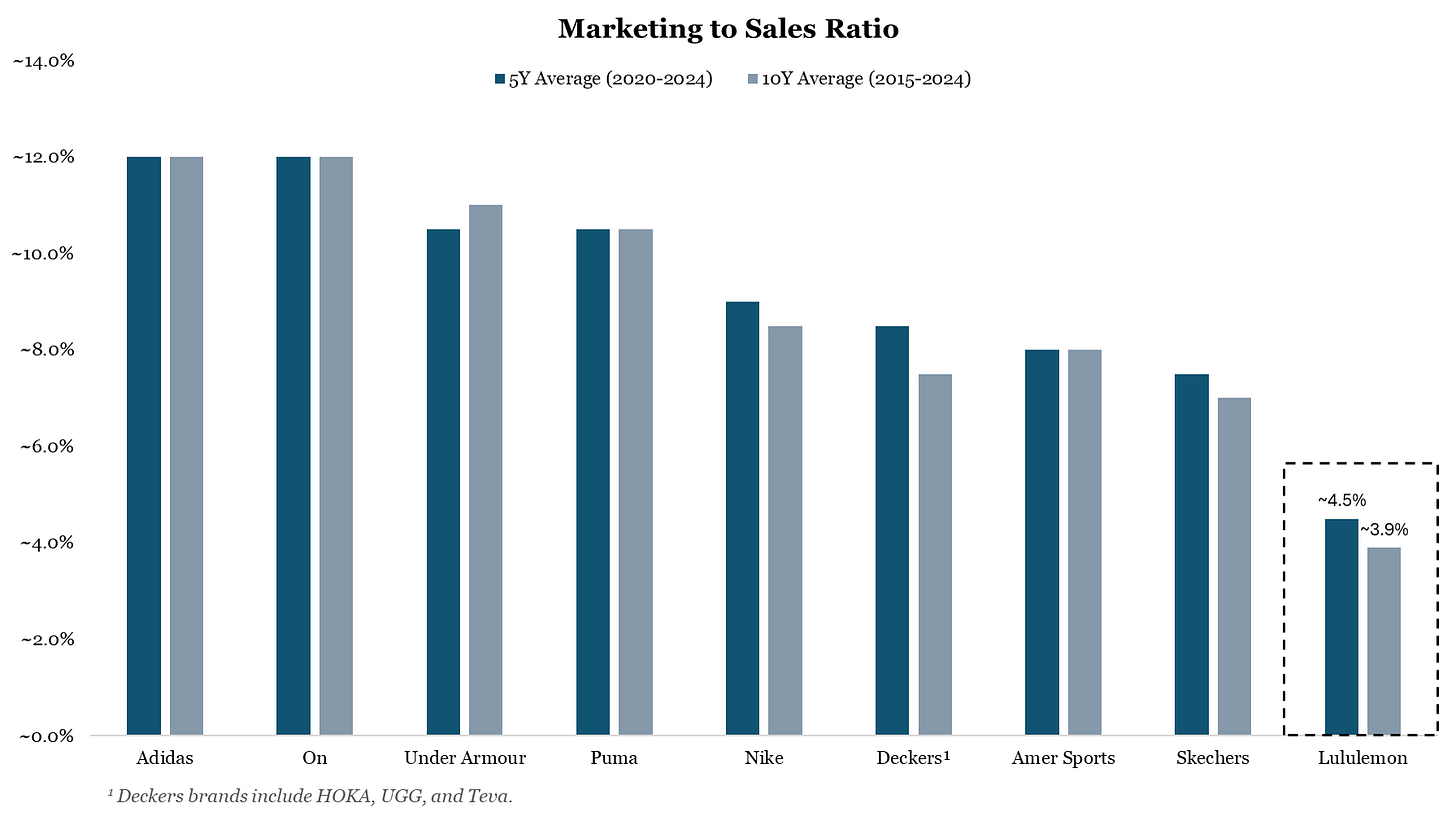

Highly profitable. Lululemon’s operating margins remain exceptional—roughly 16 points higher than peers—reflecting a business model that converts growth into profit with unusual consistency. (The company is also strikingly frugal for one so profitable—a rare and underappreciated trait, and not a coincidence.)

Store productivity. Despite industry-leading digital penetration among scaled players (~44%), stores generate nearly $1,600 per square foot—about four times the mall average.

Loyal, resilient customer base. Lululemon’s customers are exceptionally sticky. “Ninety-two percent of our loyal guests continue to shop with us year in and year out,” McDonald said in 2019. “I’ve never seen another [apparel] brand with that type of engagement.” They also skew more affluent and are therefore less exposed to economic shocks. Even in the depths of the 2009 financial crisis, operating margins held at 19%.

Marketing leverage. Lululemon’s stores double as brand billboards. Combined with strong brand equity, this allows the company to maintain marketing spend well below peers—a structural advantage that compounds returns and frees up capital for reinvestment elsewhere.

R&D edge and the flywheel. Product innovation is one of those reinvestment areas, where Lululemon invests more heavily than most. Continuous improvements sustain premium pricing and repeat purchases, which in turn fund further innovation—a self-reinforcing loop that strengthens the brand over time.

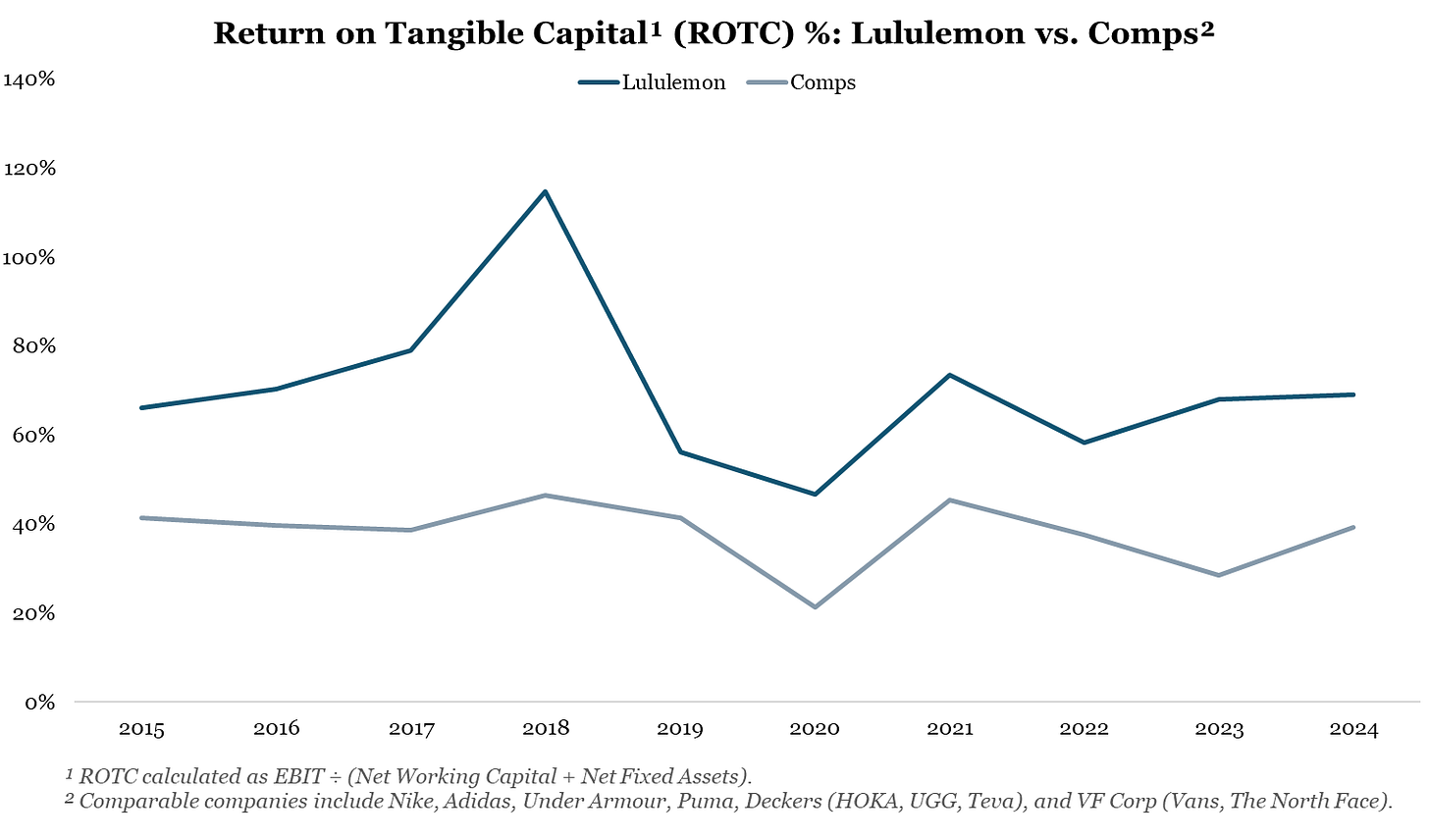

Extraordinary economics. These forces together produce exceptional returns on tangible capital, far above industry norms.

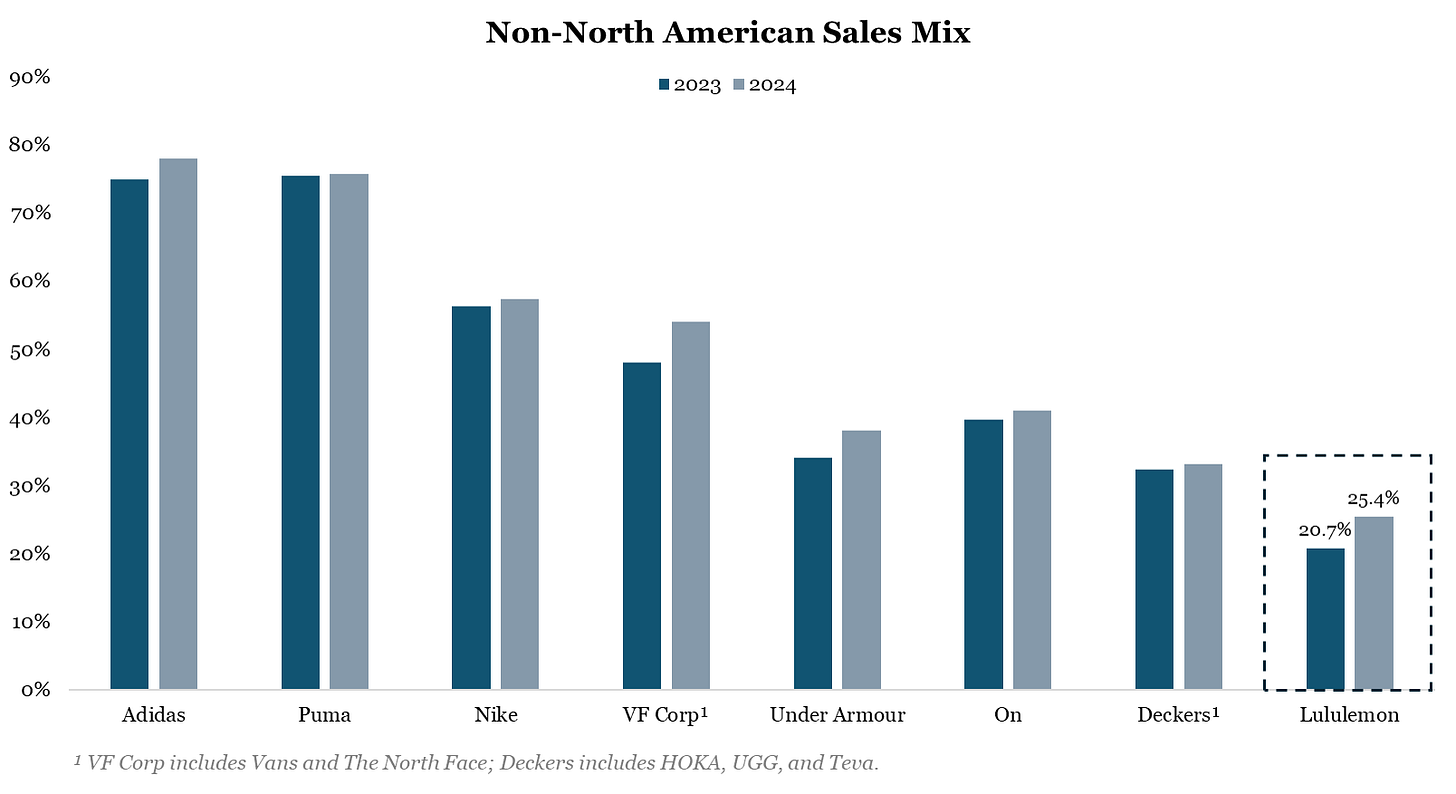

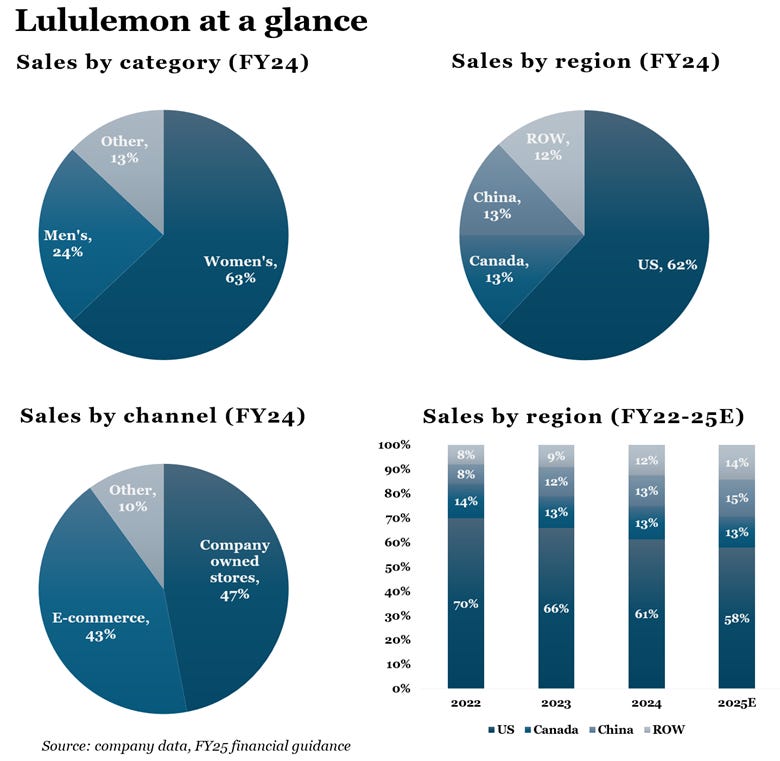

Growth runway. Only about 25% of sales come from outside North America—versus roughly 55% for comps—leaving significant international whitespace. Lululemon also remains underpenetrated in men’s, which represents just 24% of sales, well below the 50%+ typical for activewear brands (Nike is closer to 70%). Further gains are likely from co-located store expansions, which have historically driven productivity increases well in excess of the associated growth in square footage.

Financial strength and downside support. The company holds roughly $2 billion in cash, carries no debt, and continues to repurchase shares aggressively—roughly $4.5 billion since 2019—providing considerable downside protection. (The scale and prices of those buybacks have raised concerns, which we’ll address later.)

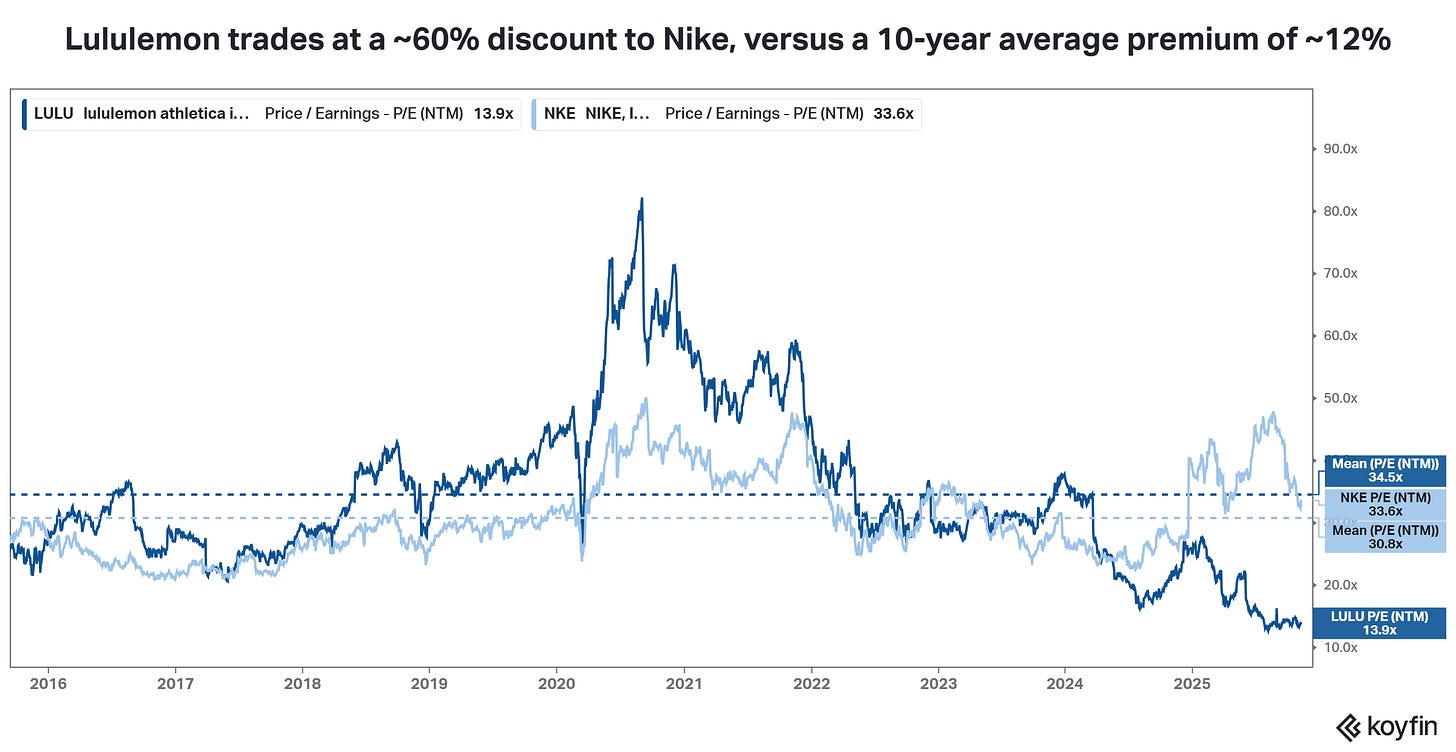

Valuation gap. Despite superior economics, vast international whitespace, and robust balance sheet, Lululemon trades at a steep discount to peers—a disconnect unlikely to last.

Lululemon also trades at a steep discount to its closest private-market competitors, Alo Yoga and Vuori, each valued in the $5–10 billion range, or roughly 5.5× sales. By comparison, Lululemon trades at just ~1.8× forward sales.

Taken together, Lululemon’s historically washed-out valuation, coupled with ample capacity for additional repurchases, provides significant downside support at current prices.

Disclosure: I and/or accounts under my control hold a position in Lululemon’s stock. This is not investment advice. Readers are encouraged to conduct their own due diligence. All figures are in USD unless otherwise noted. Some quotes may be paraphrased or lightly edited for clarity and relevance.

Brief History

“Demand and growth have been steadily up and to the right for really two decades now, and so not to say Lulu is invincible, but I have been impressed with how they’ve been able to prove their staying power over time. And I think the moment I realized that Lulu was here to stay was probably when I found myself happily spending a couple hundred bucks on their men’s clothing with many of my friends doing the same, after thinking it was a brand only for women for about a decade.”

- Shawn O’Malley, The Intrinsic Value Podcast

Founded in Vancouver in 1998 by apparel entrepreneur Chip Wilson—an eccentric and occasionally controversial figure who left the company in 2015 but remains a major shareholder (~8%)—Lululemon began as a women’s yoga line, a notable inversion in an industry long geared toward men.

Until then, leggings were simply something you wore to work out. Wilson’s billion-dollar insight was to make them look good, too. By merging form and function, Lululemon’s leggings were technical enough for the studio yet stylish enough for the street—helping ignite the trend of what would soon be called athleisure.

The company broke convention in other ways as well. It sold exclusively through its own stores, allowing it to “own” the customer relationship and cultivate an aura of exclusivity. Its refusal to discount—almost heretical in retail—only reinforced that mystique, aided by an unusually generous return policy.

Then there were the bags. The brand’s red-and-white reusable shopping totes—“the first grocery bag, at least in New York, for sure,” as one former executive recalled—became ubiquitous, doubling as both status symbols and walking advertisements.

Together, these elements gave Lululemon something rare in fashion: genuine cross-generational appeal. Ordinarily, being cool to soccer moms and cool for their daughters is mutually exclusive—but Lululemon managed both.

Over time, the company expanded well beyond women’s yoga wear—broadening its athletic range (tennis, golf), adding lifestyle apparel, and moving into men’s clothing (2014), accessories, and footwear. It would, of course, also make its mark internationally.

Company Overview and Business Model

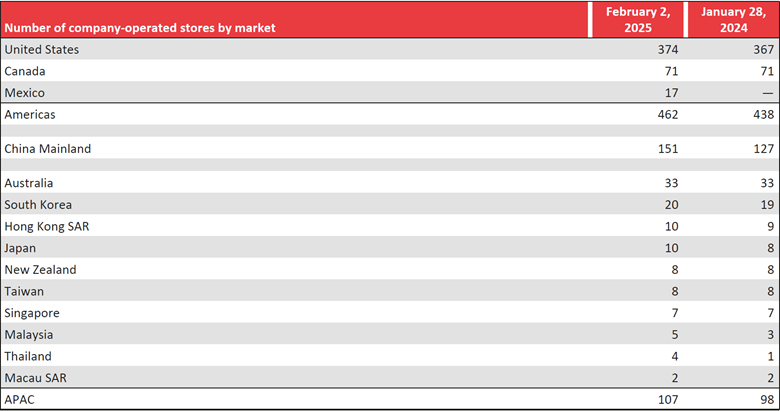

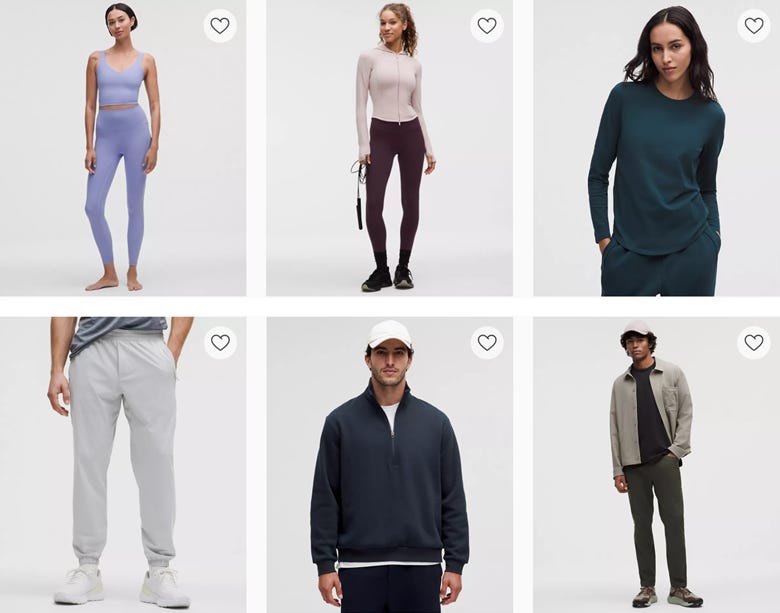

Fast forward to today: Lululemon operates roughly 800 stores—about two-thirds in North America—generates around $11 billion in annual sales, and counts 30 million members. Its product mix skews about 60% performance and 40% casual, anchored by durable core franchises; around 40% of styles sell year-round.

About 90% of revenue comes from company-owned stores and e-commerce. The remainder stems from temporary pop-ups, select wholesale accounts (including university retailers), and outlets for slower-moving or prior-season inventory—52 globally, mostly in the Americas—plus a handful of international licensees.

Over the five years ending 2024, Lululemon added 276 net new stores, roughly two-thirds of them outside North America.

Stores are concentrated in premium retail corridors—street-front locations, tier-one malls, and other high-traffic zones. Designs can vary significantly by region, but the brand identity is unmistakable.

Average store size has expanded about 50% over the past decade—from 3,000 to 4,500 square feet—through a mix of new builds and co-located remodels. While sales per square foot have remained roughly flat in nominal terms, e-commerce penetration has more than doubled—from ~21% of sales in 2016 to ~44% today (two-year average). That places Lululemon among the highest digital-mix apparel brands at scale.

It’s also one of the most profitable, with operating margins in the low 40s. That profitability reflects three structural advantages:

Unusually high customer retention

long-lived core franchises (Align, ABC, Scuba)

Highly consistent fits—once a customer knows they’re a size 30 in ABC, they can reorder online with confidence

Fit consistency, in turn, drives cross-category purchasing, while in-store returns help minimize reverse-logistics drag on margins. Lululemon’s near-pure direct-to-consumer model carries a structurally lighter net-working-capital load than wholesale-heavy peers, offset by a heavier fixed-asset base tied to its owned-store footprint. Taken together, the differences tend to net out.

Style

Lulu describes its product as “high performance, high style”—always in that order. “It all starts at the fabric level for us,” McDonald explained. “We obsess over the performance and feel of fabrics.” We’ll return to performance shortly; first, the aesthetic.

You might think of “high style” as a kind of refined minimalism—tailored fits and a quietly polished look. While more adventurous competitors might lean into bright neons or bold tri-color patterns, Lululemon’s palettes stay simple: cool or warm (not hot or cold), and rarely both. The payoff is versatility—pieces that move easily from one activity to another.

Internationally, Lululemon may adjust its assortment to local tastes, tweaking color and fit on a portion of its global line to better resonate with regional guests. In China, for instance—its most localized market—these adaptations account for roughly a quarter of sales, with another 10–15 percent designed and developed locally.

Over the past year, new styles—“newness” in industry parlance—have made up about 23% of the assortment globally. (Newness can also refer to new colors or prints applied to existing silhouettes.)

“The Bread and Butter”

“I think the fabric; that’s the bread and butter. Working at Under Armour, we had a lot of consumer insights that our fabric wasn’t where it needed to be. We used to look at Lulu and Nike and say like, “How can we replicate this?” With Lulu’s fabric, it was just impossible.”4 - Former Senior Manager at Under Armour

Lululemon sits at the frontier of technical apparel innovation—and for good reason. The company employs hundreds of specialists devoted to product development through its Whitespace Lab and dedicated R&D facilities. To put that in perspective, a director at Gap-owned Athleta explained:

“Athleta had a couple of raw materials people, but they were servicing the entire business, whereas Lulu has PhD-level scientists working on fabric innovation. That’s going to make a difference if you’re bringing your own research to the table with the mills and actually developing proprietary fabrics.”5

As implied above, most of the scientific heavy lifting in apparel happens at the mill level, not within the brands themselves. Brands typically request adjustments to an existing mill construction—tweaks to fiber ratios, yarn counts, gauges, or finishes—rather than commissioning a fabric from scratch. Any exclusivity they receive is usually brief, often limited to a single season.

Lululemon’s scale, deep supplier relationships, and collaborative development model extend that advantage dramatically—often securing exclusivity windows of 18 to 24 months or more. In many cases, it goes further still, owning the patents outright.6