Portfolio Performance Review

Up 140% since inception vs. 52% for the S&P 500

Happy New Year, everyone!

In this post, I’ll provide a brief update on the Aquitaine Model Portfolio’s (AMP) performance to date. I’ll also clarify a few points from my introductory post and provide additional context on my approach to stock selection and portfolio construction.

Revisiting that first piece, it’s clear I could have done a better job explaining what AMP is—and, just as importantly, what it isn’t—and why I’ve chosen to run it this way. I’ll try to remedy that here.

Performance

For those new here, AMP is fully invested and consists of just four stocks. The largest position accounts for roughly 40% of the portfolio; the smallest is about 10%.

As of December 31, AMP was up approximately 14%, compared with roughly 1% for the S&P 500 over the same period. While I don’t optimize for—or pay attention to—monthly or quarterly results, it’s not a bad start (or “restart”) for the portfolio.

Notably, that year-end gain added roughly 29% to total returns since inception—a neat illustration of the power of compounding. All told, cumulative returns now stand at approximately 140%, versus about 52% for the S&P 500 over the same time frame.

What is AMP?

AMP is a concentrated, long-only portfolio consisting of companies I’ve covered (or intend to cover) in deep dives. My own equity portfolio consists of the same companies, held at broadly similar weights.

The objective is straightforward: to significantly outperform the market over the long run without the use of margin, options, or leverage.

Note: Going forward, AMP’s positions and sizing will be available only to paid subscribers.

On Concentration

The more diversified you are, the harder it is to beat the market. As Bill Ruane—Warren Buffett’s longtime friend—once noted:

“I don’t know anyone who can do a really good job investing in a lot of stocks except Peter Lynch.”

I’m not Peter Lynch. But I do believe I can do a really good job investing in a small number of deeply researched businesses. While the number of holdings may grow over time, I don’t expect AMP to ever exceed 8–10 stocks.

That level of concentration naturally comes with heightened volatility, making it unsuitable for most investors. I’ve found, however, that I have an unusually high tolerance for price swings. Some of that is innate; most of it comes from (a) knowing exactly what I own, and (b) staying alert to information that might contradict my views.

That second point is crucial. According to Michael Platt—one of the world’s most successful hedge fund managers—it’s also the primary reason investors blow up. “Ego gets in the way,” he said. “They just don’t want to be wrong.”

Time Horizon

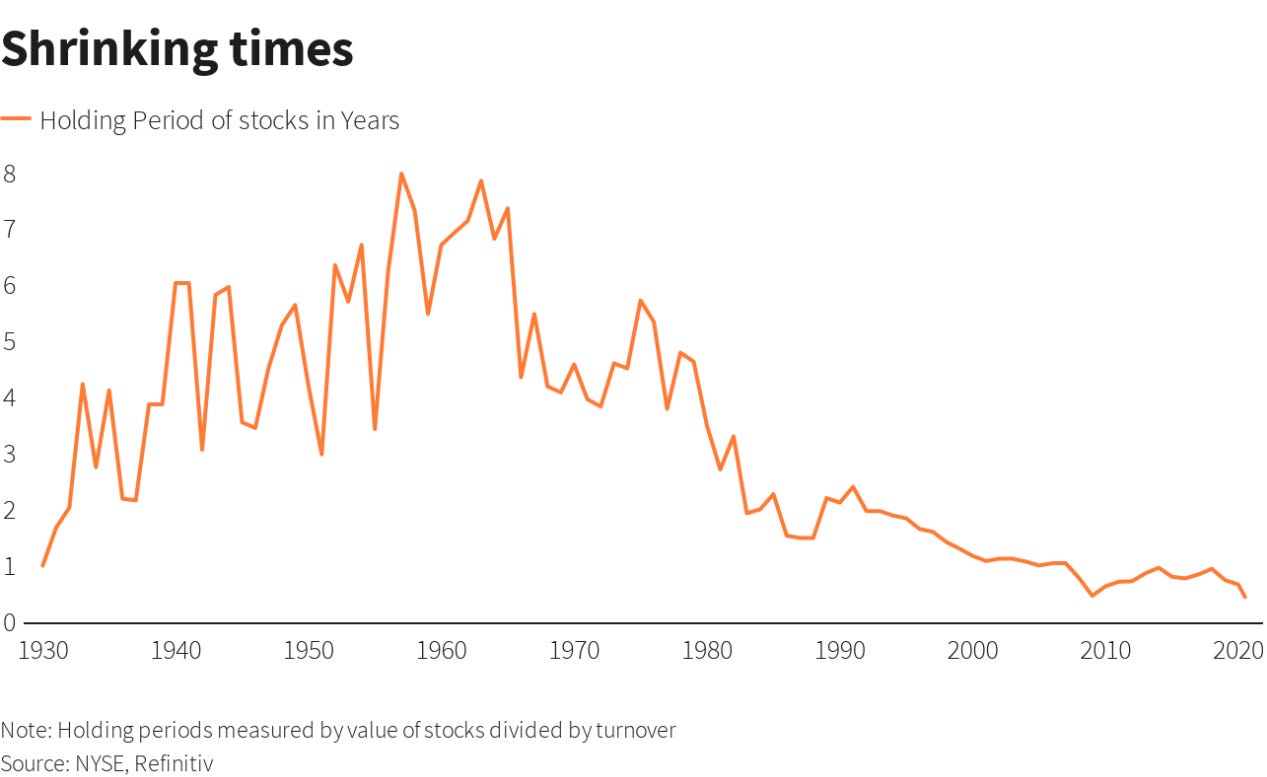

Bargains can exist even in expensive markets, but whether a stock is truly a “bargain” also depends on your time horizon. A compelling risk-reward profile over two to five years can look like a terrible proposition over the next twelve months—which increasingly appears to be the market’s default horizon.

When I buy a stock, it’s because I believe it will be worth substantially more a few years from now—preferably sooner—regardless of what the broader market does in the interim.

Portfolio Criteria

As noted in the first post, AMP holdings are not selected solely on expected IRRs. While return potential clearly matters, each position must meet three high-level criteria:

It offers a robust asymmetric risk-reward profile

I have a differentiated angle or analytical lens

It’s likely to be of interest to a reasonably broad audience

That final point generally excludes most small-cap stocks and also explains why AMP remains long-only; short ideas tend to appeal to a much narrower subset of readers.

Beyond that, several additional boxes must be checked.

Catalysts

Undervalued stocks can remain undervalued for a very long time—and the same is true in reverse. While I’m willing to wait years if necessary, I generally avoid situations where I don’t see a plausible reason for the valuation gap to narrow/close within the next 12–18 months.

Beta

(Some of you may have seen my recent note on beta. I’m reiterating it here for ease of reference.)

Beta was never something I paid much attention to—until I read Hedge Fund Market Wizards by Jack D. Schwager.

“Buying low-beta stocks is a common mistake investors make,” said Martin Taylor, a fund manager Schwager credits with “possibly the best performance record in emerging markets.” Between 1995 and 2011, Taylor generated compounded net returns of 27%—more than double the 12% delivered by the emerging-markets index.

Taylor continued:

“Why would you ever want to own boring stocks? If the market falls 40% for macro reasons, they fall 20%. Wouldn’t you rather just hold cash? And if the market rises 50%, the boring stocks go up only 25%. You get negative asymmetric returns. It’s what I call a pigeon-and-elephant trade—you eat like a pigeon and s**t like an elephant. To get equity-like returns from a portfolio of boring stocks, you have to leverage it up. If things go wrong, the loss will be massively asymmetric because of the leverage.”

His reasoning is hard to argue with: when you’re right, you want the stock to be able to really move. Of course, beta cuts both ways, underscoring the importance of buying with a margin of safety.

AMP’s weighted beta is currently around 1.25 on a one-year basis and 1.36 over five years.

Financials

With a few exceptions, the businesses I want to own share the following characteristics—or have a clear path toward them:

High normalized operating margins. There are excellent structurally low-margin businesses—Costco is the canonical example—but they rarely make attractive long-term investments. High margins provide room for error, reinvestment, and compounding.

Strong balance sheets. Minimal leverage, ideally none. If a business can’t weather a downturn without access to credit or additional equity—often available only on punitive terms—it’s unlikely to make it into the portfolio.

Management

Few CFOs are as highly regarded as Barry McCarthy, formerly the long-time CFO of Netflix and Spotify. In an interview a few years ago, he made an observation that stuck with me:

“In my experience sitting on boards—and I’ve sat on many—you never really know what’s going on inside a company, no matter how hard you try. Board members are almost entirely dependent on the management team and the CEO to assist them in their understanding of the business.

It’s a sobering reality. While this doesn't suggest we should forgo deep research—on the contrary, it is essential—it does argue for a measure of humility regarding what we can truly know as outsiders. For McCarthy, this means successful investing often boils down to one thing: backing the right leadership.

“As an outsider, you can’t ever know enough to really make an informed decision. So you need to have the pattern-matching skills to know the difference between great and not.”

This is why I spend so much time listening to—and studying—management teams. Whether it’s earnings calls, investor days, conference appearances, or media interviews, I want to understand who these people are, how they think, and what drives their decisions. When they exist, podcasts and other informal settings are particularly revealing.

Yes, it’s far more efficient to read transcripts—and I do that too. But a tremendous amount of information never makes it onto the printed page: tone, cadence, hesitation, confidence, deflection. Over time, those subtleties accumulate. This qualitative work helps me get closer to answering the questions that matter most:

Competitive Edge: If I were a competitor, would I rather square off against this team—or someone else?

Talent Magnetism: If I were a professional in this industry, would I want to work here? (Top talent, after all, wants to be around top talent.)

Capital Allocation: Do they deploy capital in a scrupulous, shareholder-friendly manner?

Engagement: Do they sound genuinely energetic and passionate about the business?

Healthy Paranoia: Perhaps most importantly, do they seem sufficiently paranoid? (Because the competition never stands still.)

Final Thoughts

As should be clear by now, AMP is shaped by a variety of idiosyncratic factors and is therefore a “model” portfolio in name only. As I emphasized in my first post, it’s not intended to be copied—even loosely—but rather to serve as a public scorecard and a mechanism for accountability around my research.

I’m excited about the work I currently have in progress, including Aquitaine’s next deep dive, which is set to be published later this week.

Until next time.

We just posted our performance since inception. The post is free to read. Check it out :)